Aleta Baun

Local leader, global inspiration

Aleta Baun, environmental activist, parliamentarian and weaver

Aleta Baun successfully led a citizens’ movement for over a decade, working to prevent four large marble mining companies from destroying the land and forests of her sacred homeland on the western part of the island of Timor, Indonesia. In 2006 she brought together 150 women from surrounding villages to peacefully protest while weaving cloth – the traditional craft of the Mollo people. After a year of non-violent occupation, the mine was abandoned and the sacred area protected. Aleta, known as Mama Aleta in her community, is now a parliamentarian representing her community against the impacts of extractives industries. By supporting women to take leadership roles and use creative protest techniques that reinvigorated traditional cultural practices, Aleta’s accomplishments extend further than just preventing mining destroying her communities’ environment to also improving gender equity, governance structures and economic development in her region. Aleta’s work offers inspiration for what indigenous rights’ and environment movements can achieve with passion, creativity and persistence.

Forest lifeblood

Home for Aleta is the Mollo region, at the foot of Mutis mountain range on the western half of the island of Timor. The area is known for being green and fertile, distinct from the otherwise dry province of East Nusa Tenggara (NTT). As well as being spiritually significant for the Mollo people, the community indigenous to the region, Mutis mountain range is also an important watershed for the Timor island. The mountains are made of porous marble towers, which allow water to permeate and drip down to follow the roots of vegetation, forming wellsprings at the base of the rock. The name Mutis, meaning ‘the flow of water’, is indicative of the function of the mountains. Thirteen rivers flow from the mountain to supply drinking and irrigation water for much of West Timor.

The Mollo people rely on forest resources for their livelihood needs, including food and medicinal products. Soil is considered to be the source of life, and the crops that grow in the rich mountain soil the embodiment of their ancestors. Natural dye is collected from forest plants, to use in their traditional weaving—a skill that women in these villages have crafted for generations. The Mollo people have a strong spiritual connection to their environment, and are believed to have occupied the land around the mountain range for more than 13,000 years. They consider the soil, water, stone and trees intrinsic to their own selves. For the Mollo people, land is symbolic of flesh, water as blood, stone as bones and forests as veins and hair. Aleta explains this relationship as fundamental to the identity of a Mollo person:

- If we are separated from any one of these natural elements, or if any one of the elements are destroyed, we start to die and lose our identity. So, we find it very important to protect the land.

A modest beginning

Aleta was born on March 16, 1966 in Lelobatan, in North Mollo, in Western Timor, into a poor farming family. While Aleta was still young her mother died, so other women and elders in her village raised her. It was from these elders that she learnt tribal traditions and values, including the sacred bond the indigenous Mollo people have with nature. Once Aleta finished high school she left her village to work in home of her family’s priest in the nearby town of Soe.

In 1993, not long after moving to Soe, Aleta became involved in Yayasan Sanggar Suara Perempuan (SPP / Women’s Voice Foundation), a women’s health NGO focused on women’s reproductive health and domestic violence issues as well as women’s working rights. SPP works to train village women and advocates for regulations in support of women and their health rights, and introduces local women to a rights perspective, especially the right to health services and legal protection. With SPP, Aleta learnt village organizing and skills for awareness raising in the community, especially in regard to women’s economic empowerment and health issues for the poor. Community organising came easy to Aleta. Being an indigenous person, she understood the issues faced by local communities and had an intuitive ability to communicate the issues experienced by villagers. ‘I saw how life was for village women. They almost don’t have strength to stand up for their rights as citizens’, she said. Her work with SPP took her back to Mollo, where she worked hard to improve the health of her community. Yet even with improved health services she observed the well being of her local community diminishing. She learnt how mining was taking place in the Mollo region and the effect it was having on the well being of the local people, both physically and spiritually.

Breaking the bones of the Mollo people

Like many of the world’s most fertile places, the Mutis mountains are resource-rich containing marble, manganese, gold, oil, gas, and many other commodities. In the 1990s a series of mining companies arrived in the office of the District Head of South Timor Tengah (TTS), who had authority to issue permits for extractive industries in his jurisdiction, which took in the Mollo region. Mining permits were issued to mine for marble in the rock outcrop complex Fatu Nausus in North Mollo, in the TTS district.

The permits were issued with little consultation of local communities. Some elders had been told that the companies where coming to make the rocks in the mountains more beautiful. Aleta explains:

- They thought that the company was there to chisel an artwork out of the rocks. For some this was the first time they’d heard of mining, so they had no way of knowing the full implications of marble mining, and what impact it could bring to their land and waterways.

As large squares of marble began to leave the mountain side however, the full implications of mining became clear to the villagers. Mining polluted the region’s major rivers, which supply drinking and irrigation water for the majority of people inhabiting the island. According to local tradition, the base of the rock is reserved for grazing livestock and it is forbidden to disturbing the rocks. The stone in these areas is considered to form the back bone of the Mollo people. Removing marble stone in Mollo tradition is equivalent of leaving a person without a spine. Local security forces were hired by the companies, with the consent of local government authorities, to guard the mine site preventing locals from planting food gardens or graze their cattle.

Aleta decided that she could not allow the mining to continue to have a detrimental impact on her community. Together with three other women, she began to organise villagers to resist the mining development. The women began by walking from village to village, in the rain and under the pounding heat of the sun with some trips taking up to six hours, to meet with the local people from the 22 villages in the Mollo territory. They discussed the history of the stone and the history of the region, and the environmental and social impacts the mining would bring to their community. Aleta felt the only way ‘to get support was to go from house to house and village to village and reach as many people as possible with our message’.

As a result of their community organising efforts, Aleta and the three women helped local elders and their communities to understand the implications of mining, and how it would affect their sacred forests and livelihood sources. In discussions with villagers, they learnt that mining was resulting in erosion, the destruction of vital water sources and forest habitat. Mollo has sandy clay soil, which is prone to erode when rocks are removed through mining. Water in wellsprings was diminishing, and many springs disappeared altogether as forests were lost. Savannah forests around the mining sites were cleared, resulting in a loss of habitat for monkeys, cuscus, civets, birds, and snakes. Villagers at the centre of the mining operations were forced to move from their traditional land without compensation. All of this to supply cut marble to the US, China, Singapore, Korea and Japan to be used as floors and kitchen tops – a luxury unimaginable to the Mollo people.

Community sentiment against the mining grew, and hundreds of villagers joined Aleta’s movement. In June 2000 they succeeded in stopping mining on Fatu Nausus. While not recognised by the district government, whose authority is below that of the provincial government, following their win Aleta announced that ‘the community has taken control of the 2000 hectares of [former mine site] land and planted corn and yams. We will not surrender the land to the government’.

But despite their win, mining continued to threaten the Mollo people’s homeland. In 2000, the same year the mine was stopped on Fatu Nausus, a Jakarta based company PT Sumber Alam Marmer was issued a thirty-year permit to operate a mine on the rock outcrop Fatu Naitapan. The mine site was located in the vicinity of the village of Tunua, within the sub-district of Fatumanasi, an area just north of Mollo. The company approached only the local tribal rajas to negotiate permission, but did not really otherwise involve important community leaders. The company promised to build houses, power plants, and a school, health clinic, church and improve the road for the local community. Aleta warned leaders of the negative impacts the mine would bring to their forest, farmland and the community, telling them ‘it's true you have money now, but you should remember that your name came from the rocks, from the tree.’ Mining supporters argued that Aleta’s attachment to Mollo traditions was out-dated and could inhibit their communities’ economic development. Fractions formed between villagers who sought employment at the mine and those who rejected the mine.

As tension grew in the community it became increasingly difficult to organise. Aleta took to organising in the cover of night, walking long distances to discuss the mine in different villages. Initially, some people in her community were critical of her organising efforts. Men and women alike harassed her. In the market place people would say hiss at her, criticising her for being a ‘bad wife’. Even her husband was not certain that organising was the right thing to be doing. When she went out at night she told him to leave the window open for her to return through. But as time went on he and her family understood what she was doing, and what mining meant for their community and began to support the mining struggle.

New mines continued to open. In 2003 PT Teja Setia Kawan, a company from Surabaya in East Java, were issued a permit by the District Head of South Central Timor (TTS) in 2004 to exploit marble in the village of Kuanoel, within the sub-district of Fatumanasi. The company began work mining the rock outcrops Faut Lik and Fatu Ob, despite protests by Kuanoel villagers. 25 hectares of farmland was cleared, an area that functions as a crucial food source for the community. Landslides became an increasingly common occurrence. Water sources became contaminated with waste rock power discharged in river ways. Drought periods intensified as well springs disappeared, forcing villagers to travel long distances to find water. The companies’ promises of building infrastructure, services and improving roads were not fulfilled, and the mining company had not employed any local people.

Aleta continued her work, building networks between villages to take a stand against the mining developments. Hundreds of villagers joined the campaign as they saw the mining companies’ promises go unfulfilled, and the negative impacts continue. They took their protest to the District Head who had issued the permit, and to regional parliament to request the mine be cancelled, to no avail. The national mining advocacy organisation in Jakarta reported the case to the Indonesia Human Rights Commission that the mining permit had been issued illegally without community consent. The Human Rights Commission issued a statement, asking the District Head to provide a detailed response about mining in TTS. Awareness was growing about the case, yet official channels were largely unsuccessful in responding to the villagers’ concerns.

Women at the front line

Traditionally in Mollo women were responsible for finding food, dye and medicine from plant sources found in the mountains. The impacts of the mines threatened the source of these forest products. They decided it was important to have the women at the fore of the resistance movements, and acting as negotiators.

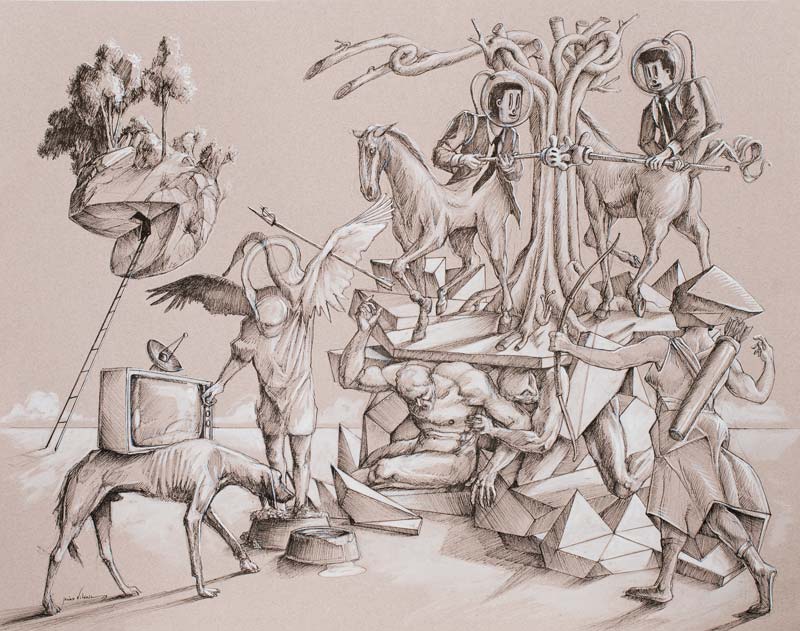

- When we began our protest, women realized that they could do more — take a stand and be heard. Women are also the recognized landowners in the Mollo culture, and this reawakened in those women who hadn’t been actively speaking out a desire to protect their land. Women decided to stage a sit in at the mining site, weaving their colourful intricate tapestries in a show of resilience and protest of the mine. Weaving brought them strength, using dyes sourced from the forests, cotton from forest cotton vines, to create vibrantly coloured patterns and symbols of their tribal totems, deeply linked to their homelands.

There was another reason for women to place themselves at the fore of the resistance movement – the threat of violence from mining companies.

- The men were fully supportive of us but did not position themselves at the forefront of the campaign because they would have likely had clashes or conflicts with the mining companies and been the target of attacks.

Inspired by the women’s leadership and actions many men from the villages took on the domestic duties at home that had previously been done by these women, cooking, cleaning and caring for the children.

Yet despite their peaceful tactics, the résistance movement became the mining company’s targets. Aleta and other protesters faced violent retaliation. One night on her way home to her family, Aleta was surrounded by around thirty thugs (called preman in Indonesian) hired by the mining company. They hacked at her legs with their weapons, and rammed her head into a tree, leaving deep scars that remain til today. Fearing for her life, she took her baby and went into hiding in the forests around Mollo. For six months she moved from village to village to escape the security forces paid by the mining company who had a price on her head. ‘Village communities accommodated me, offering food and drink and protection’, Aleta says of her time in hiding.

Unperturbed by the violent attacks, women protesters continued their mine campaign, remaining sitting at the mines, peacefully weaving their traditional fabrics. The peaceful resistance was working and the movement grew to include hundreds of villagers. By 2006, 150 women were sitting at the mine site in protest. For nearly a year the women demonstrated peacefully, weaving their traditional cloths in protest of the impact mining would bring to their sacred land. Complex logistics were developed to support women to stay in the field for days at a time weaving. Groups formed to develop protest strategy, to monitor intelligence and keep track of police and security forces, and to expand their media reach. Elders formed a group in charge of prayers and rituals to protect the safety of the protestors. The campaign caught media attention domestically and internationally, and the pressure on the mining companies’ mounted.

In the face of the villagers’ peaceful and sustained presence, and with growing public awareness of the weaving campaign, marble mining became an increasingly untenable endeavour for the companies involved. In 2007, the mining companies, responding to the pressure, stopped mining and by 2010 all mining operations was abandoned in the region. Finally, after more than a decade of struggle, Aleta’s movement had successfully pushed out the mining companies. Indonesian government officials returned the mine sites land to the Mollo traditional land owners.

In a region rich in resources Aleta recognises that there will continue to be businesses interested in digging up the rocks and clearing the forests precious to the Mollo and other communities in TTS. To strengthen themselves in anticipation of future mining prospectors, the Mollo people are mapping out their traditional land – key to having their land rights recognised and protected by law, and important protection against future developments. Mapping land rights is the first stage of a joint land rights claim between three communities, in order to place the land under collective ownership of these communities.

To restore the watershed function of the upstream region of Mollo, Aleta is supporting her community to use traditional seed collection techniques to reforest areas cleared by mining, and rejuvenate water sources. Already 15 hectares of degraded mountain land has been restored, reviving dozens of dried springs. 6,000 people displaced by the mining across the region have been resettled in their traditional homelands. A portion of the abandoned mining sites have been set aside as learning places, reminders of the destruction of mining for future generations faced with mining pressures.

Aleta is also working to improve her region’s economic prosperity to ensure that the Mollo people are not forced into accepting extractive industries to escape poverty. ‘Poverty drives people to exploit natural resources, and in the process destroy those resources and divide communities – pitting elders against community members, and communities against other communities,’ says Aleta. To create economic opportunities for villagers through sustainable farming and enterprises that generate income from weaving and other activities, Aleta and her team of activists formed an indigenous association, called the Organisasi A’Taimamus. The group takes in around 500 working groups across the 22 villages of the Mollo region. The group works to support sustainable farming and other sustainable income-generating activities, including empowering women through supporting weaving enterprises. The group provide legal advocacy and a credit union to support small businesses.

In 2013, Aleta won the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize for her grassroots work. The $175,000 prize award is the world’s largest award honouring grassroots environmental activists. Aleta used the prize funds to support the work of Organisasi A’Taimamus to conserve and reforest areas that were destroyed by mining operations, and to protect local land from future mining projects and threats from commercial agriculture and oil and gas development.

In 2014, Aleta was elected as the parliamentary member for NTT provincial parliament for the period 2014-2019, one of only five women out of a total of 65 members. In her role as parliamentarian, Aleta is prioritizing protection of ecological functions in NTT, so that farmers that rely on water catchments and fertile soils can continue to maintain their livelihoods. She is also working on legislation to recognize and protect adat communities’ forest and land rights. In addition to raising three children, Aleta recently pursued her dreams of going to university and completed a law degree at a university in the regional capital of Kupang.

References:

http://www.britannica.com/biography/Aleta-Baun

http://www.goldmanprize.org/recipient/aleta-baun/

http://indonesiaexpat.biz/travel/solid-as-rock-mama-aleta-guardian-of-timors-sacred-towers/

http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2013/04/18/aleta-baun-environmental-heroine-molo.html

Como citar

Toumbourou, Tessa; Maimunah, Siti (2019), "Aleta Baun", Mestras e Mestres do Mundo: Coragem e Sabedoria. Consultado a 15.07.25, em https://epistemologiasdosul.ces.uc.pt/mestrxs/index.php?id=27696&pag=23918&entry=31052&id_lingua=1. ISBN: 978-989-8847-08-9