Tran Dan

Life and Voice

Tran Dan (1926-1997) was an exceptional Vietnamese poet and novelist who inspired generations of Vietnamese for his leading voice in defending the artistic and creative freedoms of writers and artists during the dark years of the 1950s in communist Vietnam. Being persecuted, imprisoned, and banned from publication throughout his life for his critical stance against the domination of artists and writers by the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam, he remained nonetheless “a literary leader in the dark,” in the words of prominent contemporary writer Pham Thi Hoai, for incessantly striving for creativity in his poetry and for his unwavering faith in truth, humanity, and love.

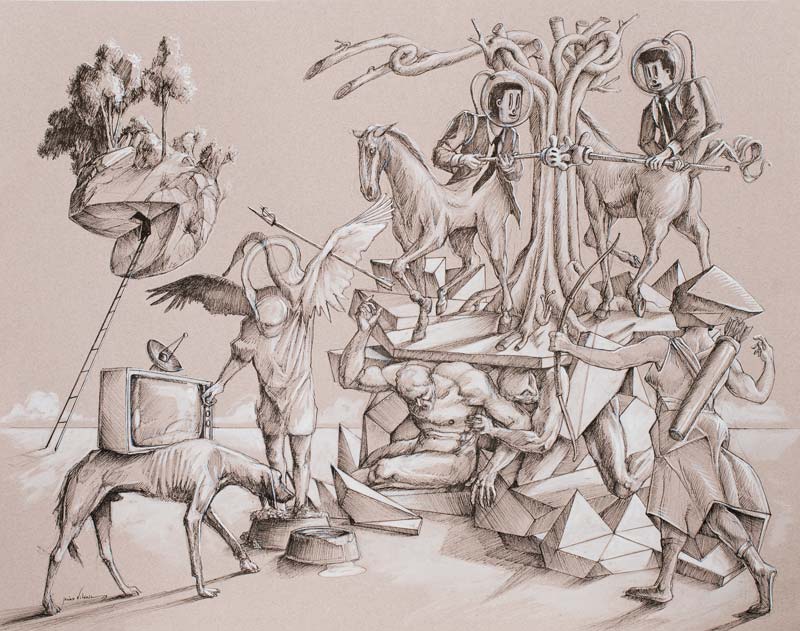

Tran Dan was born in 1926 in Nam Dinh, Northern Vietnam, in a well-to-do family. He attended high school in Hanoi and there obtained a French baccalaureate. He started composing poetry early and formed a symbolist poetry group with other fellow poets when he was 20 years old. When the Anti-French Resistance War broke out in December 1946, he returned to his hometown of Nam Dinh to join the resistance and assumed a propaganda commissar position. After Nam Dinh fell, Tran Dan joined Ve Quoc Doan (the National Defense Brigade) and served in both combat and propaganda duties in the northern border area. He was admitted to the Indochina Communist Party in 1949. In 1950, Tran Dan co-founded the first Army Arts and Letters group. However, Tran Dan’s stairs poems and cubist drawings were considered difficult to understand. As disagreement with political cadres of the regiment deepened, Tran Dan applied to transfer to the Office of the Arts and Letters of the Army’s General Political Department. There, from 1951 to 1953, he was responsible for the political education and training of performing artists who would serve in the army. But he was again criticized for teaching the performing artists the “wrong” Party policies.

In 1954, Tran Dan volunteered to join the Dien Bien Phu operation, together with the famous painter To Ngoc Van. To Ngoc Van’s death during the operation affected Tran Dan deeply. He wrote and published Nguoi Nguoi Lop Lop (“Waves upon waves of men”) in the very same year. It was the first novel about Dien Bien Phu, about the heroism of ordinary people in the making of the victory. However, despite belonging to the victorious side, he still doubted the price of war and longed for peace. He wrote in his diary in September 1954, four months after Dien Bien Phu:

Someone said, “the war trains people.” Yet why do I only talk about loss, desperation, superficiality, panic? I think what they said is true, and what I say is also very true. […] Yesterday we were very very heroic. We starved ourselves. We wore torn clothes. We worked even in the absence of the minimum necessary conditions for such work. We got rid of many ugly characters – the quiet-seeking spirit, the selfishness and shyness. We suddenly and intentionally trained ourselves to become courageous, altruistic, self-sacrificing. […] But I say we are lost and desperate. I am not talking of our houses, health, of our youth and families, of properties or physical well-being. What I am talking about is our soul, our thoughts, our emotions. I am talking about the life of the mind of each person. […] Yes, the war trained us. […] The war made us stronger in our flesh and bones, it gave our soul a frame, a good and solid frame. But don’t mistake the skeleton for the body, and the frame for the soul itself. […] You say the war trains people; you should think Peace also does, and it does so even more effectively. […] I think, nine years building peace are definitely better than nine years clenching our teeth in a resistance war. Not only is it better on the material plane, it is also better for our soul. […] We would have had factories, […] we would also have had bookstores full of books, publishers working hard to meet the demands of the public, art exhibits in the autumns, concerts, […] we would have had peasants learning to drive tractors to plow, discussing theories and technology, and being able to read novels and Marxist philosophy... The past nine years should have been like that. […] That is the level I set for our people.

And in October 1954:

In the last days of the War and the first days of Peace […] in my mind I already take stock, sum up, think, feel bothered about many issues. […] (When I wrote Nguoi Nguoi Lop Lop, those issues already luxuriantly sprouted all over my soul.) […] For example, the issue of freedom to create, the issue of writings and the responsibility of authors towards the truth, and the issue of love. I’ve found out, or, rather, I’ve pointed out more clearly what I’ve always loathed: - censorship that is, - médiocrité dans l'art that is, - the deception, formulistic direction in life and in the arts…

In October 1954, after the success of Nguoi Nguoi Lop Lop, the government invited Tran Dan to go to China to write and record the script for a commemorative film about Dien Bien Phu. Accompanied by a political cadre and closely controlled on the content and even on the way to write the script, he left China to go back to Hanoi in December, deeply frustrated. He started to organize discussions with other artists on the needed changes in the army’s arts and letters policies. He wrote in his diary on 20 December 1954, upon his return:

It has been exactly 10 days since my return to Hanoi […] The arts and letters agency has not changed. […] Still the restricting, imposing, and dogmatic “militarizing the arts and letters” policies. My life is drowned in these policies, just like others’. Very difficult. But I heard many voices rising. Protesting. Debating. Mocking. And even cursing. This means the drumbeat that announces the death of the oppressing thoughts and policies towards the arts and letters in the army. How sad I’ve been these recent days. A sharp pain in my brain. And I am irritated. Agencies and policies. The arts and letters association lost my draft of Nguoi Nguoi Lop Lop (parts 4 and 5). The debt of the government, childhood memories, bitter and intense, the writhe of the nine years of war. My poems they neither refuse nor wholeheartedly print. Many projects are hard to carry on because of the constricting policies: building a new life requires freedoms. I’m under siege. Too tight. Too constraining […] What do I want? – An open arts and letters policy, to make it right. A creative life, rejecting what’s already old. […]

In April 1955, Tran Dan and five other colleagues submitted a twelve-page “Draft Proposal for a Cultural Policy” in which they demanded that the leadership of the arts and letters be returned to artists and writers, that an arts and letters branch of the Arts and Letters Association be established within the army without being controlled by the Army’s General Political Department. Tran Dan also laid out his thoughts on the responsibilities of the writers in the Proposal.

The highest manifestation of the responsibility of the writer is respect and loyalty to the truth. That is the highest standard to evaluate authors and their works… Respecting and abiding by the truth are at the same time the responsibility, the stance, and the working method of the writer. […] What is loyalty to the truth? But, first of all, what is the truth? There is the truth of the cosmos, of history, of the world, of the revolution. There is also the truth of a country, of each locality, of each industry, each circle, of each family, and each person. In each person there are millions of matters, each matter is itself a truth […] That is: the issues, the phenomena of the society, of man, are the truth. […] The truth that is millions and millions of times larger than any decree, any theory… If the truth is against policy directions, one must then write the truth instead of bending the truth to fit the policies. Never turn policies and directions into “taken for granted” preconceptions. […] The writer only writes because of the urge of the truth. He, with self-awareness, finds small or grand universal truth in life, in army duties. He doesn’t write to please the propaganda committee, the superiors.

Dan also asked to leave the army and the Communist Party of Vietnam. He married his girlfriend Bui Thi Ngoc Khue despite the Party leadership’s disapproval of the marriage because Ms. Khue’s Catholic family migrated to the South after the Geneva Accords. As a consequence, for three months, from 13 June to 14 September 1955, Tran Dan was detained and was forced to write a “self-criticism” report – a self-reflection on what he was doing wrong.

In January 1956, Tran Dan’s poem Nhat Dinh Thang (“We Must Win”) appeared in Giai Pham Mua Xuan (“Masterpieces of the Spring”), an independent publication of like-minded prominent writers and poets who also upheld the flag of creative freedoms against censorship. His poem reflected the conflicting thoughts of the poet vis-à-vis the condition of the country, placing his own personal tragedy against the general backdrop of the tragedy of his divided country. It was a moving account of both despair and hope. Throughout the poem are beautiful imagery and touching emotions of the hardship of his personal life, the struggle to get by amidst the ruins of the post-war North, and the hardship of his people in a divided Vietnam after Geneva.

I live on Sinh Tu Street:

Two people

A small house

Full of love, but why was life not joyful?

Our country today

although at peace

Is only in its first year

We have so many worries…

…

I was living with frayed nerves

A time dense with conversations about going south

The rain kept falling darkly

People kept dragging themselves away in groups

I became one who carried anger

I turned my body to block their way

– Stop!

Where are you going?

What are you doing?

They complained of lack of money, of rice

Of priests, of God, of this and that

Men and women even complained of sadness

– Here

They longed for the wind, for the clouds…

Oh!

Our sky faces a cloudy day

But why abandon it when it is our sky?

…

Who led them away?

Who?

Led them to where? And they kept crying

The sky still lashes down heavy wind

North and south, heartbreaking division

Kneeling down, I ask the rainstorm

Not to continue falling upon their heads

– enough hardship!

It is their bad fate – don’t punish them further

Neglected gardens and fields, empty houses

People are gone but they leave behind their hearts

Oh northern land! Let’s safeguard for them

I live on Sinh Tu Street

Those sorrowful days

I walk on

seeing no street

seeing no house

Only the rain falling

upon the red flag1

The magazine was recalled and Tran Dan’s poem was vehemently attacked by members of the Association of Arts and Letters for “distorting and vilifying the situation in the North.” He was accused of criticizing and doubting the Communist regime by repeating the “negative” image of the rain falling upon the red flag. Because of the poem, Tran Dan was imprisoned in Hoa Lo prison for three months, during which, fearing he could be quietly murdered without anyone knowing, he attempted to cut his throat with a razor to be transferred to the hospital. Only in October 1956 did the Arts and Letters Association acknowledged its mistake in criticizing We Must Win. The Masterpieces of Spring was reissued with the poem in it. Between October 1956 and early 1958, dissident intellectuals were also able to publish and circulate several issues of liberal literary magazines such as Nhan Van (“Humanity”) and Giai Pham (“Fine Arts”).

Starting July 1958, however, the grip of official censorship tightened again. In a purging campaign known as the Nhan Van-Giai Pham affair, many writers and artists who were part of Nhan Van or Giai Pham were suspended and disciplined. Tran Dan was expelled from the Writers Association and was suspended from publishing for three years. Between August 1958 and 1960, as a disciplinary measure, he was sent to several hard labor and reeducation courses with other writers. All the while, he continued to write poetry and started composing a poetry-novel entitled Cong Tinh (“Provincial Gate”). In August 1960, during a hard labor reeducation course in Thai Nguyen, he fell very ill and returned to Hanoi.

Starting in 1960, Tran Dan stayed outside of all mainstream arts activities and earned a living by translating books. He silently and consistently continued to write and experiment with new poetry styles. He finished the poetry-novel Cong Tinh in 1960, wrote Dem Num Sen (“Night Lotus Bud”) – a novel, in 1961, Jo Joacx (poetry) in 1963, both Mua Sach (“Clean Season”) – poetry and Nhung Nga Tu va Nhung Cot Den (“Crossroads and Lampposts”) – a novel in 1964, and many other works until 1987. He also consistently kept an annual journal every year from 1954 to 1989, that he named “Notebook of Poetry,” and, from 1973, “Notebook of Dust.” They contained his notes and short verses and reflections on life, individuality, and poetry.

It is not until after the Renovation reform of 1986, which partially abolished the crumbling centrally commanded economy and allowed for private enterprise, that the intellectuals associated with the Nhan Van-Giai Pham affair started to be invited to join mainstream literary activities again. In 1991, Tran Dan’s epic poem Tho Viet Bac (“Viet Bac poem”) was published in Hanoi. The poetry-novel Cong Tinh was published in 1994 and earned an award from the Vietnamese Writers’ Association.

Tran Dan passed away in January 1997 in Hanoi. His poetry collection Mua Sach was posthumously published one year after and was highly praised by writers in Vietnam for its originality. Another collection of poems, Tran Dan Tho (“Tran Dan Poetry”), was allowed to be published in 2008, only to be fined and banned from distribution for “violating the publishing policy” shortly thereafter. The Ministry of Information and Communication stressed that the ban was not because of the content but because of a violation of the publishing procedure. With almost 500 pages, it was the most comprehensive and sizeable publication of Tran Dan to date. Despite a life of hardship and persecution, Tran Dan’s writings always remained the truthful expression of his faith in love, individual freedoms, and humanity, even if these themes were often intertwined with strong emotions of sadness, pain, and solitude.

I’m tortured by individualism

I defend sorrow and solitude.

Defend dew-coated lamp posts

lonesome stars at the corner of the sky. (Tho mini 1988)

I cry for the horizons where no one flies

Then I cry again for those who fly without a horizon (Tho Mini 1988)

The communist regime succeeded in imposing physical restrictions on his career and personal life, but it failed in constraining the artist’s spirit of freedom which continued to soar highly and candidly in the creative realm he preserved for himself. Tran Dan’s uncompromising devotion to poetry and writing as the absolute expression of individuality, as well as his boundless creativity and originality, remain the inspiration for generations of Vietnamese who treasure freedom.

Who said I’m poor? Dangling moon and stars I have. Endless clouds airing all over the horizon. My offerings, which warehouse is big enough to keep them? A whole universe with plenty of stars. To whom should I leave this behind? Layers upon layers of clouds, continent after continent of richness. (So Bui 1979)

Notes

- See the full translated poem in Tran Dan, We Must Win, 1956, in Ghi, 151-64; trans. Kim N. B. Ninh, in Sources of Vietnamese Tradition, Eds. George Dutton, Jayne S. Werner, and John K. Whitmore, 530-36.

References:

- Trần Dần – Ghi, 1954-1960, ed. Phạm Thị Hoài (Nxb td, memoire, Paris: 2001)

- Black Dog, Black Night: Contemporary Vietnamese Poetry, eds. and trans. Paul Hoover and Nguyen Do (Milkweed Editions, Minneapolis: 2008).

- Tran Dan, “We Must Win,” trans. Kim N. B. Ninh, in Sources of Vietnamese Tradition, eds. Jayne Werner, John Whitmore and George Dutton (Columbia University Press, New York: 2012).

- Tran Dan, Two poems: Đoạn kết – Unite; and Tình yêu – Love, translations by Jason Gibbs, available at http://taybui.blogspot.com/2008/12/hai-bi-th-trn-dn.html (2008).

Love - by Trần Dần (translated by Jason Gibbs)

sent to K for those days we're apart

My dear

I couldn't sleep

for four days!

I miss you

Sinh Từ road

that blackened my nose

coal smells

dust smells

I miss the room

now

pacing in silence

you alone

Dear

Has love ever been smooth?

It suppresses waves

suppresses the rain

storms surge...

Love

is not a matter

of giving each other

every day a bouquet

It's a matter

of nights fully

sleepless

hair disheveled

like rows of tall trees

it convulses

nights of bracing winds

Love

is not

reverie shoulder-to-shoulder

sad dreams under a worn out moon

but must live

must expose itself

to rain and sun

must sweat

flow, flood

clear to the liver

Love is not

a thousand year story

cheek-to-cheek

but suddenly -

one heart held common

must cleave it

make

a pair

one person half

one person

holds the other half close

Love

is not

the blackened cars

of life's train

though the journey

is for cutting off

or for joining

But in itself it's

the LOCOMOTIVE

of a thousand cars

at times - bright

at times - unlit

A million horsepower

a crazed train

foolish train

it crashes

shatters legs

day and night

it howls death

time

distance

it screams out

upon earth

before man

before society

before principles

conditioning...

Love isn't

random acts, how is love

fine

it's strange

like being midst a starry sky

millions of lights

It's only I

have made myself hoarse

screaming

just able to call out

your - star - that

often cries

And with you

gone forever for to paralyze

me

just pausing

to hold me tight

dejection

my - star - is

burnt out

scorched in the sky

Love

whether it

exists or not

it's fine

and it's like

lines of poetry

the muscles

the nerves

fatherland

*****

My dear

you're crying again

dear?

An empty room

the lying dog, it howls

I've just punched at the sky

a half dozen blows

when will I

sit

die

a room

four walls

hold back body

mine

cede my education about many matters

and the love story

- is the story of us

Do read carefully

this page of poetry

Count up

the letters

the rhymes

are like so many nights

you gave at the starry sky

you've seen

a star

swaying

it's - my - star

changed to four in the sky

chase it off - yes it's

a vicious star

I'll allow you

to cry alot

cry some more

my dear

your love

will never ever age

ten centuries

star

mine

still burns…

Como citar

Nguyen, Huong (2019), "Tran Dan", Mestras e Mestres do Mundo: Coragem e Sabedoria. Consultado a 09.07.25, em https://epistemologiasdosul.ces.uc.pt/mestrxs/?id=27696&pag=23918&id_lingua=2&entry=36618. ISBN: 978-989-8847-08-9